Welcome to R!

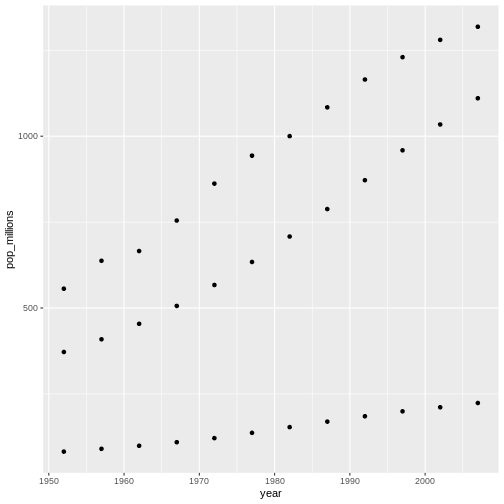

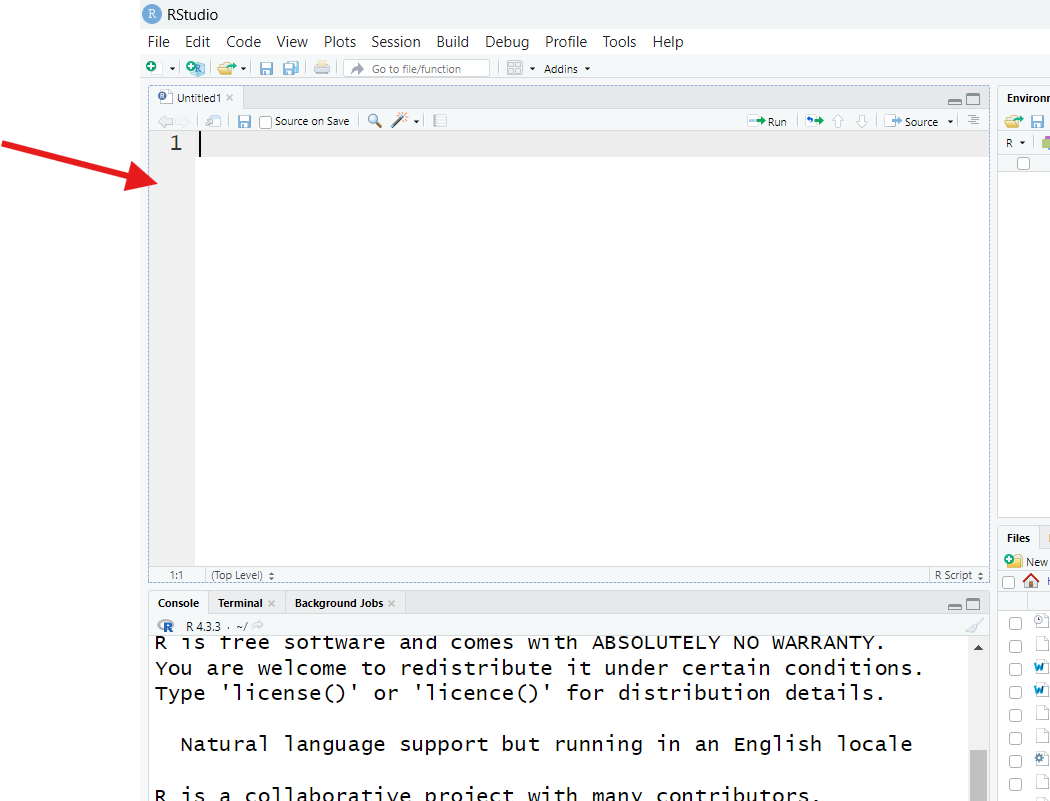

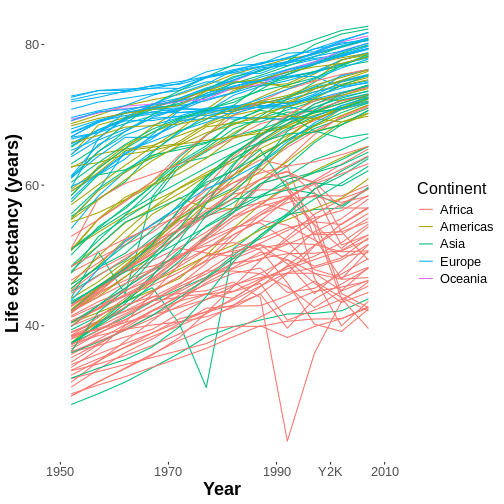

Figure 1

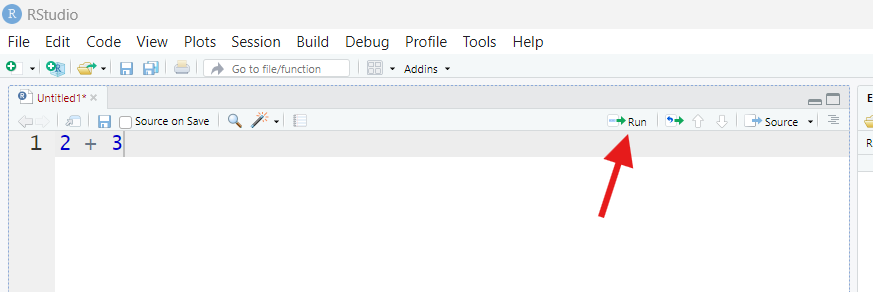

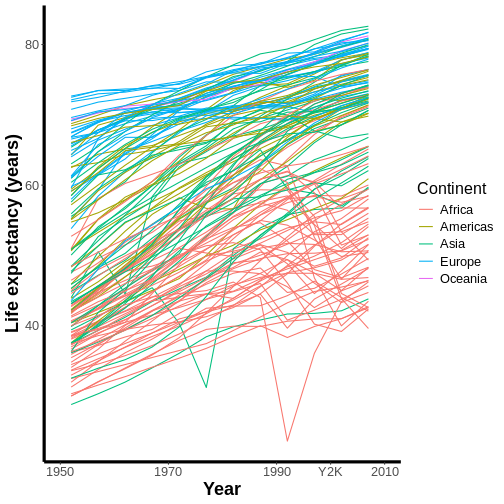

Figure 2

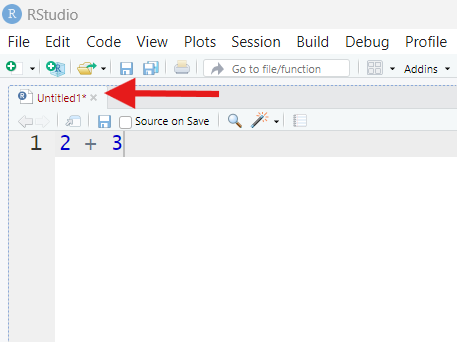

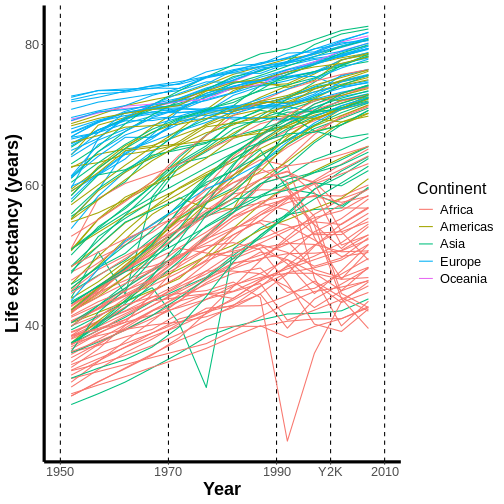

Figure 3

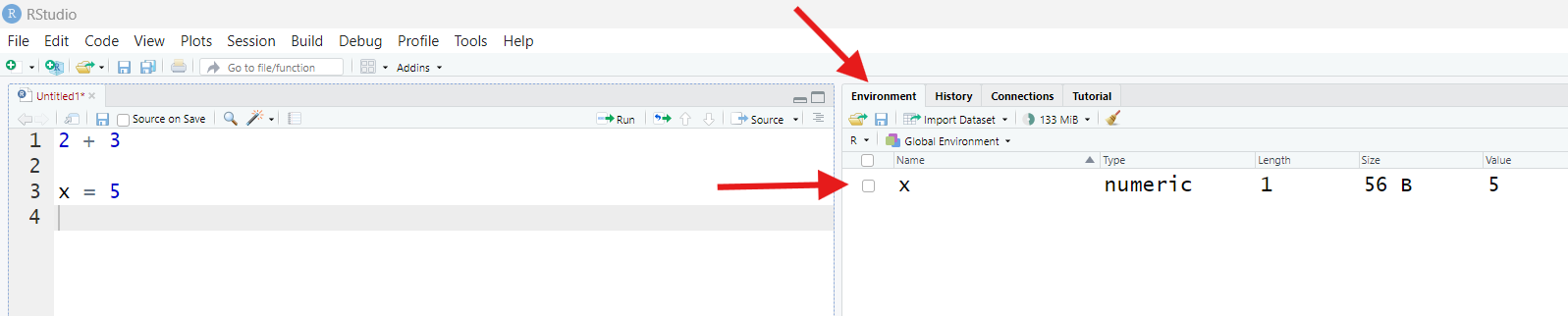

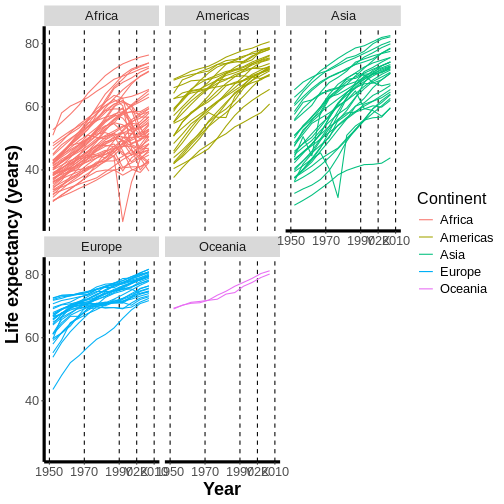

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Exploring the Tidyverse, a modern R "dialect"

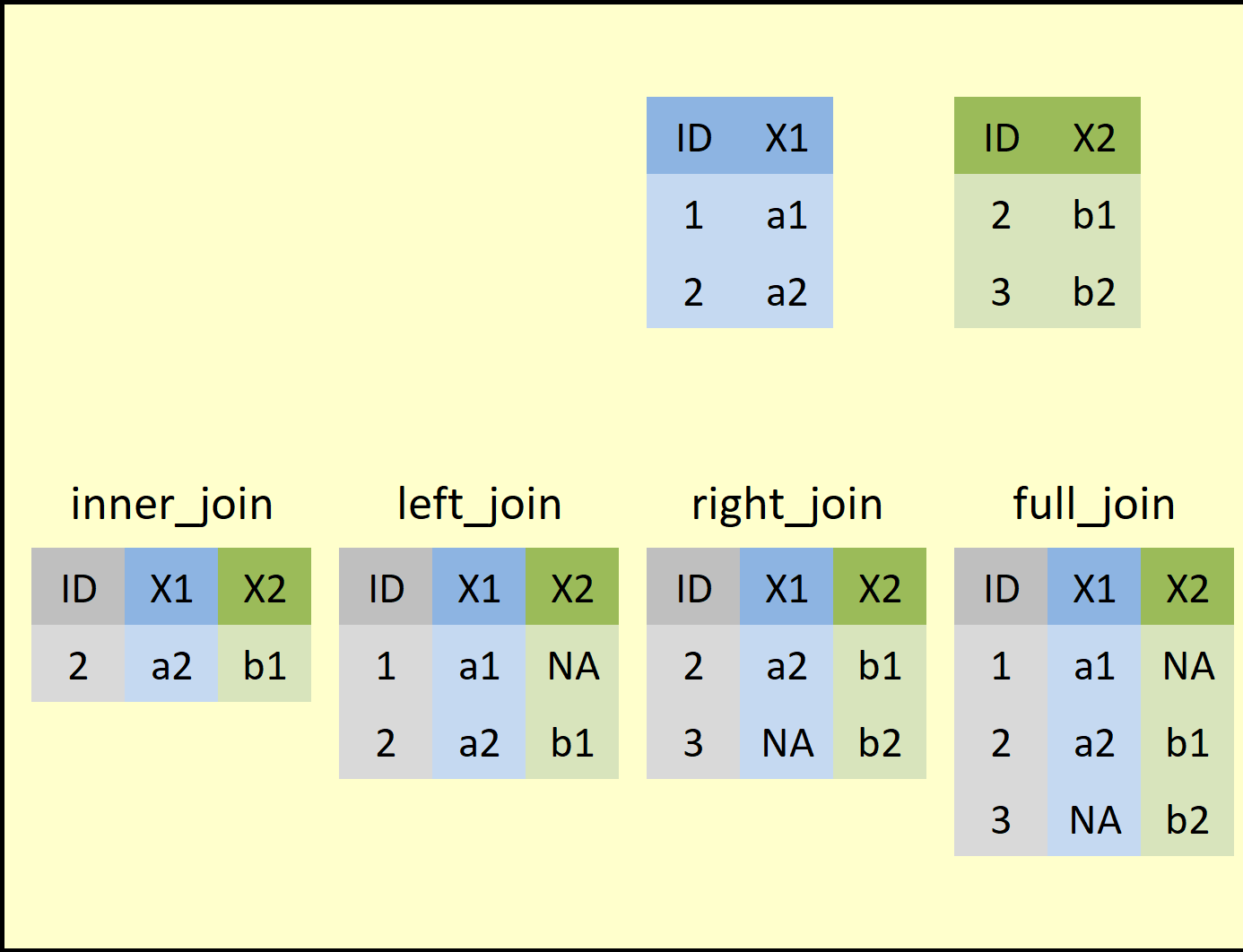

Figure 1

A diagram showing the most common types of

joins. On the top are two small data tables (a “left” table in blue and

a “right” table in green). A left join keeps all the rows in the

left-hand table and adds any matching data to those rows found in the

right-hand table (any missing data implied by the join gets marked as

NAs). A right join does the opposite, keeping only all the rows in the

right-hand table. An inner join will only keep rows that have a match in

both tables, and a full join will keep all rows from either table

whether they had a match or not. A “match” is determined by whether or

not the values in key columns (here, the two ID

columns) match between the left-hand and right-hand tables. In this

example, row 2 of the left table and row 1 of the right table match

because they have the same ID value, so all joins will unite the data in

these two rows in the product.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 26

Figure 27

Figure 28

Figure 29

Figure 30

Figure 31

Figure 32

When data are in a wide format (left-hand side

above), groups within the data (such as teams) have their own rows, and

everything we know about each group (such as stats) is listed in

different columns in that group’s row. When data are in long format

(right-hand side above), each individual row belongs to a single

observation, i.e one datum (such as one particular record of one

statistic) and columns instead hold information about what groups each

statistic belongs to. Same data, different organizations!

Control Flow--if() and for()

Figure 1

If you’ve been to an amusement park, you’ve

probably seen a sign like this one before. It may not seem like it at

first, but this sign is an “if statement!”

Figure 2

If you’ve ever been to a deli counter or the

DMV, you’ve probably seen a ticket system like this one. This is just a

for loop!

Vectorization

Figure 1

Figure 2